_Roy Amara_

We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.

[Wikipedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Amara)

The changes that are now happening in the IT industry with the AIs and LLMs are so significant that I find myself repeating myself in various groups and places so I will just write down my thoughts here so I can share them publicly.

First thing first: I have no idea where we are heading exactly - I am only like 75% sure. There is still a lot of uncertainty but I think at the end of 2026 we will have 95% of the picture clear. I have my bets and opinions but take them with caution as a lot can change in 2026. The pace of innovation is super fast right now.

Software Engineering is not going anywhere. The industry is facing a huge transformation. This is not the first transformation, this industry is changing constantly. However this will be a different one, that is a bit scary but also exciting.

Fundamentally it won't change our relationship to work - we were always doing the work to solve problems and deliver value. But it will change what is considered a valuable skill, how work gets done, and where the opportunities are.

The winners of this change will be the people that can figure out which parts of the Software Engineering job won't be commoditised by AI, and how the work will evolve as we move forward.

Foundational engineering knowledge will still be super important, even with LLMs and AI, as it will make our collaboration with agents much more effective. But the role of software engineers will mean less coding, more guidance, review, and decision-making - figuring out the "what" and "why" versus the "how".

There are 3 AI camps.

We are Doomed.

In this scenario, I’m assuming we reach AGI and AI simply replaces us. But looking at recent evaluations, like METR’s assessment of OpenAI’s GPT-5.1-Codex-Max, current LLM systems are still incapable of generating serious problems for us. And if we look at benchmarks like ARC Prize, we’re still far, far away from reaching AGI, at least based on the way we currently measure what AGI is. Based on AI 2027, there is also a scenario that we have paradise enabled by AI, but it also implies that the industry as a whole is gone.

AI is a fad that will fail.

In the past, there were two major AI winters. It is possible that another one is just around the corner. There are already experts who argue that LLMs are not AI and are going to take us nowhere. That the path to AGI requires more breakthroughs. I can’t argue with that, as I am not an expert in this field all I am interested in is on how to use the current generation of AI/LLMs in my field of expertise.

I think we’re long past the point where we can assume that this generation of LLMs is a failure. Based on my experience and people around me, there is a lot of utility and value already there . The discussions in my circle are more about - how to use it? What are the good practices? What will be the new design patterns we should adapt to? Instead of - oh it is just a hype.

Also, based on the Can AI scaling continue through 2030? It looks like we will be able to scale AI training runs to 2030. At the moment, it looks like there is no major bottleneck apart from the “AI is a bubble” burst, which might slow things down. But the “AI bubble” is just a course correction and is more about hype and investment promises made to investors not about the usefulness of this technology.

AI is useful and will transform the market

I support this team and will expand on it in next sections.

Transformation - nothing new in IT

This is, of course, obvious, but the market is constantly changing. If you look at the overall employment history of Tech related roles in the US, you see roughly a steady growth. I couldn’t find exact data for software engineers, but these roles did follow a similar curve.

Based on this chart, we can assume that demand is growing constantly. But this view hides a lot of complexity. Defining what the “software engineering” role is, is simple when we think about generic terms like building software. But uderneath when we think about programming languages, specific skills or practices used in this field, the view gets a lot more complicated.

What the market actually demands shifts constantly.

This shift can be observed in programming language popularity. The TIOBE index shows how languages rise and fall over time. The industry was once dominated by Java, C, and C++. Now Python sits at the top - likely driven by demand in data science and AI.

The growing demand is spread across different programming languages needs based on market needs.

My personal experience: The first language I have used commercially at work was JavaScript with JQuery (old times). Then I moved to C# / .NET world for a couple of years. There was some time with more of JavaScript (Angular/Reac), and I moved to write software in Golang, Java, Python, or even Lua. I also spent multiple years writing HCL (Terraform). These days, I mostly write code in C#, Golang and Python.

A similar picture does come up in the skills area - from Manual QA to Test Automation, DevOps, and DevSecOps. A lot of the current demand requires new types of skills that we had to acquire over time.

My personal experience: I have started as SharePoint Developer long time ago, then I jumped into fullstack ASP.NET world. I was a huge advocate of TDD. As the industry changed, I was an early adopter of Docker and the cloud. Even thought i spent a lot of time in C# oriented companies, I have never used Azure but AWS. With time, I discovered the beautiful world of distributed systems and I focused more on DevOps/SRE oriented work. Today, I would consider myself to be a generalist.

And last chart methodologies - once we were dominated by waterfall, which then change to agile and scrum.

My personal experience: I had the opportunity to try Waterfall (It wasn’t as bad as the current myths portray it). But I entered the market with already big ideas like DDD, Agile on the horizon, so it was easy to switch over to it.

Why does transformation happen? Competition → Commoditisation → Innovation

Transformation isn’t unique to tech. It’s a core part of our economic model and arguably part of being human. We evolved in a competitive environment, under constant pressure from natural selection. That same pressure drove us toward collaboration, cooperation, and eventually organizing ourselves into societies. In the market, we are in a constant cycle of: Competition -> Commoditization -> Innovation.

Here is what I mean: A company discovers a new need in the market, creates a product, and this brings profit. Other companies see it and start competing. Competition drives down margins, and the product becomes commoditised - meaning it is not special anymore. To escape low margins, you need to innovate. Find novel ideas to create new value. And the cycle repeats.

_What about `monopolies`?_

I know, I know - this is much more complicated, and competition is not as clear. There are specific markets dominated by single companies (either a whole segment of the market or geographically), and even in the past goverments had to interveene in order to open up the competition as Big players always have an incentive to control competition and the market itself.

One great example from my country was forcing privatization of the main telecommunications company in Poland to open up the market (which was very successful for the economy and the consumers).

But as a principle, competition as one of the main market drivers, in general still holds.

Software development was always under transformation pressure.

Now, as software engineers, we might think this doesn’t apply to us. We are engineers, and all of the transformations were driven by innovation and people wanting to do things better. Some of it, sure. Open source is a perfect example of people building better tools because they wanted better tools. But a lot of innovation was driven by the market.

The software development process has always been expensive and was considered to be a pain point to get around. Designing systems, writing code, testing, releasing to production - all of it costs time and money. And you know what? building the software was never the overall point. The goal was always to build a product and Software development was a necessary cost to get there.

Companies, individual engineers, entire communities - felt pressure or a need to innovate to bring the cost of development down. To make the work easier as there was a lot of value waiting to be captured from the market:

- New programming languages made it easier to write code

- Frameworks like the JVM handled memory management, so we didn’t have to

- Languages like Go and Erlang targeted concurrency as systems grew more complex

- Ruby and Python optimized for productivity and speed of delivery

- Cloud made it simpler to orchestrate complex architectures without the need to deal with racks and

realhardware - DevOps popped up to bring engineers closer to infrastructure

This was a difficult truth for me to accept. As an engineer, I wanted to believe the craft itself mattered the most. It took me some time to realize that the market doesn’t care about things like Software Craftsmanship or how elegant the code is.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that we can just YOLO with software development, but there is a term I like to use called Good Enough Software that puts a lot emphasis on Engineering Talent to decide how to develop software in a scalable, maintainable, sustainable way - depending on the context - market, product, and organisation you are in.

The case of Cloud, Kubernetes - abstracting away complexity

Each wave of transformation abstracts away complexity and shifts where the value is created.

Cloud and Kubernetes are good examples here. Initially, only the biggest companies could build globally scalable and reliable product. They had the resources, expertise, and infrastructure to do it. But as internet usage grew, more companies needed ability to do this. AWS capitalized on this - opening up their opinionated approach in the form of the cloud.

It solved one problem, but as complexity grew, new problems appeared. So the market responded again: orchestration systems to manage the chaos. And then we got Kubernetes. I know - Kubernetes is complex. It’s not “easy.” It’s sometimes overused. But here’s what it did: it commoditised the ability to build global, scalable, reliable systems. What was once the domain of really Big Companies became accessible to a much broader market. This shifted where the hard problems lived - and where the value was created.

The case of Manual -> Automated -> AI driven testing

The folks before cloud will tell you that, in some way, their skills were commoditised. But this change also increased demand for more complex products. If you were willing to learn, you could capitalise on the shift. The market rewarded those who adapted.

A similar thing happened in the world of manual testing. When I joined the industry, testing was typically done by a dedicated role. You had developers and you had testers - two different jobs with separate responsibilities. Then a change happened, and in the org I was part of, Manual QAs were forced to learn programming while programmers were told to get better at testing.

The need to merge these two positions was most likely caused by a push to speed up development. Back then, there was a big push to break up silos of responsibilities - developers vs testers. When testing happened late in the SDLC, issues were discovered too far down the pipeline, causing costlier changes. This led to the “shift left” movement: pushing testing responsibilities closer to design and development phases. The idea was simple - find problems earlier, fix them cheaper, automate most of the boilerplate tests and increase both quality and velocity.

Microsoft formalized this with the SDET role (Software Development Engineer in Test), explicitly encouraging the move toward automated testing. Eventually, even that role disappeared - absorbed into the broader Software Engineer title.

The chart above shows this transition with Manual QA skill demand in a steady decline. with the skill becoming easier to get on the marker. This led to a drop in value generated by this specific skill. Test Automation, on the other hands was under-supplied with demand growing over time. This led to growing adoption of test automation.

We are very likely right now on the verge of another shift - towards LLM driven testing.

A pattern that appears here is:

- New skill needed → is under supplied → generates high value

- People learn new skills → supply grows → value normalizes

- Next shift arrives → previous skills demand lose steam -> and you need to adapt

_TDD is not about testing_

Around the same time, the TDD movement started. But it's important to remember that TDD was never about testing! Yeah, a shocker - but really, in my opinion, TDD was more about iterative discovery of the problem space and code design.

It was a way to quickly verify your assumptions about both the solution and the code. Easily testable code was usually well-designed code, so you felt motivated to write simple code - it enabled simple tests and improved your velocity.

Transformation is an opportunity (+ stress and uncertainty)

There are two ways to approach transformation. You can treat it as a risk - a threat to your ability to generate value, a force that might make your skills obsolete. Or you can look at it as an opportunity. I prefer to look at it from an opportunity angle.

Of course its not easy to just say - well, adapt - learn new skills. I am almost 40, and I don’t have the same energy that I had in my 20s. By saying just treat is as an opportunity, I’m not being an asshole or a smart-ass. I really do understand this is stressful. It’s not easy to just “adapt” or “learn new skills” when you’ve spent years building expertise that suddenly can potentially become less valuable or no longer a thing that differentiates you in the market. But I don’t think there is anything else we can do about it. The market will just do its own thing - and force us to transform.

This opportunity is also time bound. Meaning that the earlier you go along with it, the more value you will get. If a practice brings value and productivity boost, the market will not just sleep on it. Early adopters are the ones that have it more difficult to adapt, but then best practices develop, tooling is being created, and as an industry we build this collective intelligence and understanding that makes it a lot easier to get into - changing something that was a differentiating factor to a baseline, average skill.

But i It can also be risky, as when you are an early adopter, you have no idea if this specific new wave or hype will stay and develop to something more serious and there is a risk that you might have wasted your time. But personally I don’t think it is a big deal, as you have still learned something new and expanded your knowledge.

_You should always have some risky bets in your career_

Think of it like investing. You diversify. Some skills you go deep on, hands-on. Others you keep an eye on, waiting for the right moment to commit. Not every bet pays off—but having no risky bets at all is the riskiest position of all.

I believe AI will transform our industry. It will make us more productive, more impactful, and ultimately more rewarded by the businesses we work for. But to benefit from this shift, you’ll need to transform yourself. You’ll need to become a different type of engineer.

_IT is in a pole position_

Being in tech means you're in pole position to see what's coming. We're one of the first industries adopting AI at scale. That puts us in the early adopter bracket of a technology shift that will eventually hit every industry. A lot of sectors will face this challenge in 5–10 years. By then, we'll have already lived through it and experienced it ready to share our knowledge and experience.

AI / LLMs transformation

Before we can jump into some conclusions or advice’s on how the next transformations might look like, lets get some things straight first.

Software engineering was never only about coding

Code was always a tool, a way to orchestrate 0s and 1s to fulfill business needs - not the goal in itself. Software engineering has always been about building things and solving problems that humans face. All economic activity is ultimately driven by human needs, our job is to figure out and build systems to provide for this need.

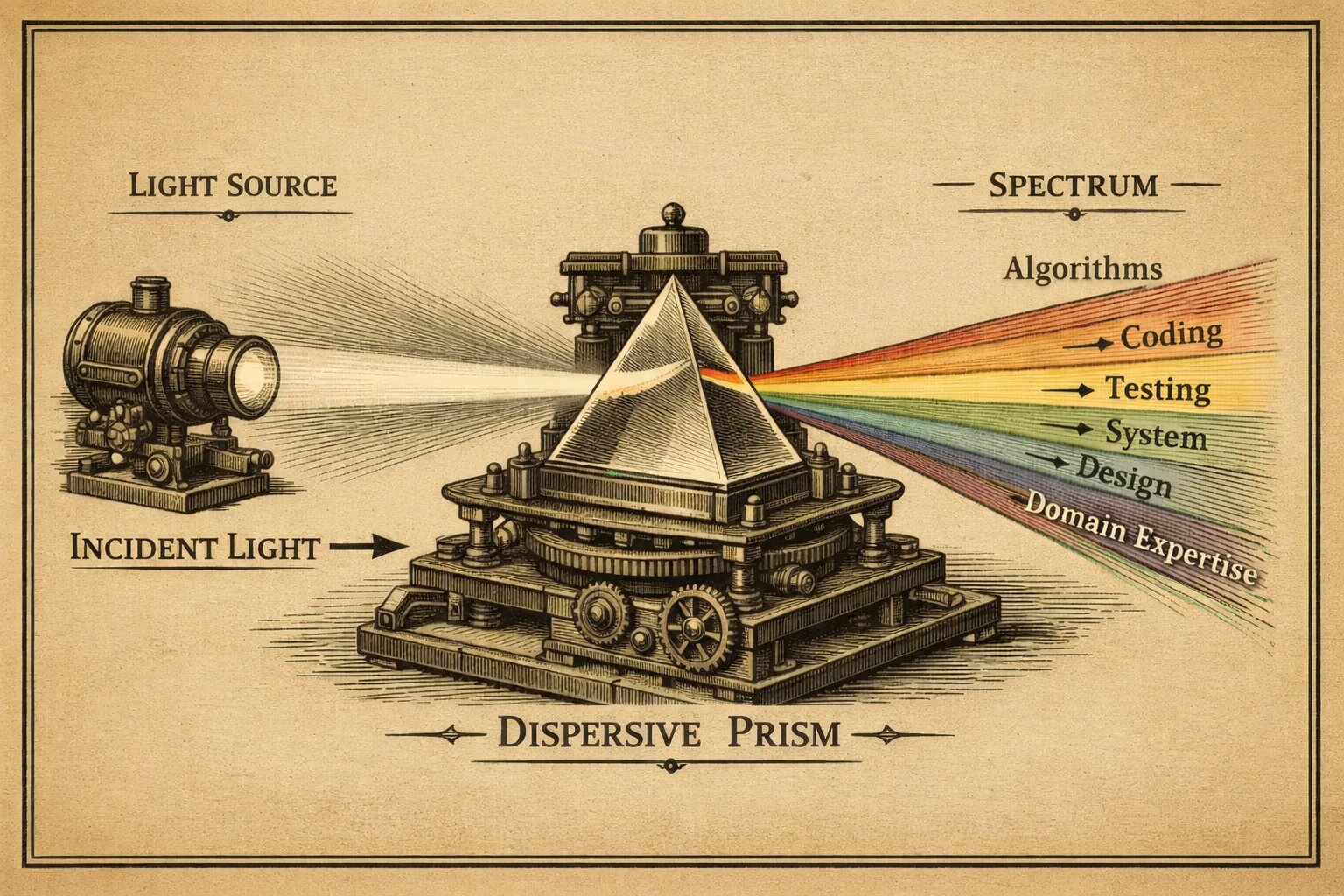

The early career model from the past put a lot of emphasis on coding and computer science. This skill-set was usually the first step on the ladder and one of the main reasons engineers of my generation got hired for. But along the way Software Engineering role has become a lot more than just writing code or obsessing about algorithms.

These days, there is a lot of time spent on designing systems, figuring out trade-offs, communicating with stakeholders and team members or even customers. You need to plan the work and advocate for features or changes. You can also get involved in changing the processes or guidelines for the rest of the team. A significant amount of time is spent reviewing code or ideas. We also need to spend time figuring out how to be effective in the organisation - every company is usually different and has a different culture that you need to adapt to.

The job was always bigger than just writing code. And this is great news, it means Software Engineering will not disappear.

The bottleneck of software engineering of tomorrow will move up. Thanks to AI and LLMs, coding will no longer be the limiting factor. But that doesn’t mean it’s smooth sailing from here - it just means that we will hit new (or old) constraints with higher force and frequency.

The ability to frame and decompose problems will become the new limiting factor as LLMs reward precise intent and clarity. Vague input produces vague output.

Same with maintaining product quality, reviewing changes, navigating operational constraints, and understanding your organisational context and requirements. All of this will still require a human engineer to deal with.

_Autocomplete didn't make us 10x productive_

I remember when autocomplete was becoming popular. There was this feeling that we'd all become much more productive. But it turned out it was not the case. There were benefits, but autocomplete was was not as transformative as a lot of people thought. It has helped us with just part of the day-to-day work.

The core of software engineering was always about delivering value

It is just that there was a time when we could pretend it was not.

I remember the golden age of my coding-focused engineering career. I could happily code and code and only code. Everything else was handled by the organisation. The business analyst prepared a huge spec, the scrum master or EM created tickets - all I would do is just get the ticket code, leave it for the tester, and jump into another ticket.

From this Point Of View, it kind of looked like my job is about coding, but behind the scenes, someone else was translating my work to actual value delivery. As I grew and joined more product-oriented companies, I started doing more and more tasks not only related to coding and getting involved in a whole spectrum of tasks required to build successful product.

I think the AI and LLMs will serve as a great equalizer here and will force a lot more engineers to start thinking about all the different tasks and skills they never had to think about before. This is one of the things I have noticed in US Big Techs - push towards - it’s your responsibility to understand what kind of impact and value you bring to the table.

The good thing is that - with this mindset, we will be able to generate even more value.

OK Michal - so much talk - get to the point - what should I Do?

Yeah, that is a question, the main one, that we will need to find an answer to in 2026.

To be honest, don’t listen to me you have to kind of figure it out for yourselves and adapt it to your career and context. But if you are interested to check what I am planning to do or what I would do - keep on reading.

Beyond Hard Skills

I really love this chart from Alex Ewerlöf. It helped me a lot when thinking about the choices I should be making in my career.

Investment in hard skills at some point reaches a moment of diminished returns. To be fully clear, it doesn’t mean you should ignore it completely. I still do it, you still need to keep an eye out for emerging trends and technologies. Try out tools, new languages. But for instance, learning Java to the book if you already know C# - does it make a difference? I don’t think so.

AI and LLMs will also bridge the hard skill gap across languages and frameworks. The specific flavor you know - .NET, Java, Python - will matter less and less. Marketing yourself as “I’m a .NET Engineer” or “I’m a Java Engineer” is probably not going to be an effective strategy going forward. The market will care less about what you can code in, and more about what problems you can solve, and what value you can deliver and what is your expertise (more on this later).

So maybe it’s time to spend more time building Soft and Business Skills as they will provide more value and substance in the work you do.

I also encourage reading this series from Alex:

- Senior to Staff Engineer - Alex Ewerlöf Notes

- Beyond Staff Engineer - Alex Ewerlöf Notes

- Principal Engineer - Alex Ewerlöf Notes

_LLMs will not make Hard Skills Obsolete_

This is an important point to make. I don't think hard skills will go away even with AI and LLMs. In order to properly work with AI, you still need to understand foundational knowledge (Algorithms and Data Structures, Distributed Systems). Learn at least one programming language and different paradigms of programming. Build a lot of projects, solutions, and make a ton of mistakes. Only with that kind of knowledge and experience will you be able to use AI and LLMs effectively.

Foundational Engineering Knowledge

Another set of skills that I don’t think will go away is Software Engineering foundations.

This foundational knowledge enables crisp and intentional communication with AI agents. You’ll understand how to frame problems better, how to validate the output, and what kind of questions to actually ask. Without it, the chance of ineffective prompting increases. So the more foundational knowledge you have, the more effective you will be when working with AI agents.

Algorithms and data structures are here to stay. But the knowledge that matters is not memorization of algorithms or the ability to pass interviews (it is now popular to frame this as “interview-passing knowledge”). What actually is important is getting an intuition and understanding of trade-offs mixed with real-world usage examples.

It is much easier to reason about database engines and indexes when you know the basics of self-balancing trees like B-trees. Another example: HyperLogLog. You’ll hit rough edges using Elasticsearch if you don’t understand probabilistic data structures. Another: vector databases. Understanding how they work makes it much easier to figure out what’s happening behind the scenes with LLMs and all their “magic”.

Software Quality / Verification

There will be more code produced and faster iteration on building things, but this will hit the testing and reviewing wall. This part of the SDLC will become an even higher bottleneck. We’ll also spend more time designing “AI-legible” code - clean abstractions, consistent patterns, and clear boundaries - because, in my opinion, well-structured code leads to more effective work with LLMs.

This means that knowledge around testing, software verification, and how to build simple, well-modularized codebases will be even more valuable.

Distributed Systems and System Design. This knowledge helps you understand how to build complex systems - and what is even more important, what physical limitations we cannot cross (in our universe), no matter how beautiful our solution is or how clever the design is.

Understanding CAP theorem and PACELC helps you build a simple (or maybe a bit complex) mental model on the tradeofs available to us as engineers and how to reason about them. ACID vs non-ACID helps you figure out why NoSQL databases appeared and when to probably use them.

Similarly, you won’t fully grasp the importance of load balancing, fault tolerance, or what a transaction actually is and why it matters - without understanding the theory. Same with consensus algorithms like Paxos and Raft, or concepts like leader election. They’re the foundation of every complex system you’ll ever build or work with.

Without this knowledge, it will be much more difficult for you to understand how to design systems that are durable, available, and scalable. AI agents will easily fool you and set you on a path that will not lead to an optimal solution and basically waste your time - assuming you even know what questions to ask in the first place.

And most importantly, without this knowledge, it will be much more difficult to reason about various trade-offs. Which, frankly, is the most important skill for engineers. I mean answering the question, what is a good enough system we should build given our context, domain, market, budget, and team. And how to reason about it, make a decision, and then sell this decision to everyone else.

Example of potential things to read and learn from:

- Distributed systems for fun and profit

Basic but great overview - a good starting point. - Database Internals

A lot of details - but if you want to understand how the Database Engines work - I think it is one of the best resources right now. - Raft

Great visualization of RAFT and distributed consensus. - Designing Data-Intensive Applications (DDIA)

Great book - which for me is like a road-map. The book itself is not really comprehensive, but it provides a great starting point plus is full of references that you can use to learn more. For me its like amapof reading about how to build complex systems.Domain Expertise

I already mentioned that one option for engineers now is to go beyond hard skills. This is where Domain Expertise comes into play.

What do I mean by domain expertise? (Examples not exhaustive)

- If you are a frontend engineer, you have built a ton of systems that users interact with. The next step is learning UX design and figuring out what makes an interface actually work for people.

- If you are a backend engineer, you have spent years building the logic that runs the business. Now dig into the business itself - which metrics matter, and what drives them? What is your business moat? What is your advantage?

- If you work in medtech, fintech, or any other specialized area - get more involved in it. Understand what makes this industry competitive on the market.

This way you will learn about what to build and why. With LLMs gaining traction, we will spend much more time focusing on answering exactly these types of questions and getting closer to product and decisions being made. The real value of a developer is working together as a team with business-oriented team members. LLMs will be a final nail in the coffin for a SDLC model with siloed teams specializing only in one specific area like - we are writing code or we are writing specs. It will just not scale well.

There is an argument that: “What prevents business-specialized people from working with LLMs directly?” Well, I think you need hard skills and engineering experience to work effectively with LLMs, especially on harder more complicated problems.

This isn’t a new idea - Eric Evans preached this in his Domain-Driven Design book years ago. We just need to get back to this foundation.

Final note: Becoming AI Native

As a 40-year-old engineer, this is an important point to make. I have experience and knowledge. I have built things in specific ways, and I acknowledge the fact that after so many years in the industry, I like to do things a certain way (I use Vim every day and despise working without i3wm and a proper Linux setup).

So it will be important for me to challenge my habits and the current “neural network structure” I have in my brain. I just barely feel like I am treating AI tools naturally and not as a novelty, nice-to-have thing or skill. The way I did it is I forced myself to use AI and LLMs even if my brain was suggesting it’s not productive, a waste of time, or that the results are bad. With time, I started noticing patterns on how to get better results, and this now serves as a reinforcement mechanism - I see benefits, I learn more, I use it more, I get more familiar and natural with it.

I really think that “becoming native” with the new way of building things will be important, so that you can leverage it to the fullest and not fall back to well-known patterns - as they might not be optimal after the transformation.

Summary

Oh that was long I know but hopefully you found something useful here.

_Summary_

---

**Main Thesis:** Software engineering isn't going away, but it's undergoing a significant AI-driven transformation. The winners will be those who figure out which skills won't be commoditized by AI.

**Three AI Camps:**

1. "We're doomed" (AGI replaces us) - unlikely based on current evaluations

2. "AI is a fad" - we're past this point; there's real utility

3. "AI will transform the market" - the author's position

**Key Insight: Transformation is Normal**

- Tech has always evolved (languages, methodologies, skills)

- Pattern: Competition → Commoditization → Innovation

- Cloud/Kubernetes example: complexity gets abstracted, value shifts elsewhere

- Manual QA → Test Automation shows how skills rise and fall

**What Won't Be Commoditized:**

1. **Foundational Engineering Knowledge** - Algorithms, data structures, distributed systems, CAP theorem. Not for interview prep, but for intuition and trade-off reasoning.

2. **Software Quality/Verification** - More code means more reviewing and testing bottlenecks. "AI-legible" code design matters.

3. **Domain Expertise** - Shift from "how" to build to "what" and "why". Frontend → UX design. Backend → business metrics. Understand your industry.

4. **Soft & Business Skills** - Hard skills hit diminishing returns. Problem-solving and value delivery matter more than language expertise.

**Becoming AI Native:**

Challenge ingrained habits. Force yourself to use AI even when it feels unproductive. Over time, patterns emerge and it becomes natural.

**Bottom Line:** The role evolves toward less coding, more guidance, review, and decision-making. Focus on what problems you solve, not what language you code in.